Just before Halloween, I published what started out as my valiant attempt to challenge the belief that investing in a 401k plan is the better of the retirement income strategies when you compare it to a regular taxable stock-based account. In case you haven’t read it yet, please feel free to check it out here.

While I thought I had put forth a good effort, I was humbly delighted to receive a number of comments that pointed out several flaws with several of the assumptions I used to reach my conclusions. After looking more deeply into a few of the more constructive comments, I decided it was worth it to correct my wrongs and give this exercise another go!

I’d like to extend an especially big thanks to reader Lucas for all the guidance he provided on helping to get these calculations right. I believe this time around the model will be far more realistic and indicative of what would actually happen in real life. And as we’ll discuss towards the end, that could have serious consequences on how we decide our save our money going forward!

Why Care So Much About the Difference Between These Retirement Income Strategies?

Even though I mentioned my rationale in the first post, I feel it’s important enough to bring up again.

Why care so much? Well, first of all: Because it’s MY money!

I see investing in taxable stock market accounts as being an absolute critical element to a successful early retirement plan. As you probably know, you can’t access your 401k or tax-sheltered plan without penalty until you are age 59-1/2. That’s not very helpful if you plan to retire in your 50’s or 40’s.

So my goal to all this is to find out: What would happen?

If I invest in one versus the other, will it make that big of a difference? Will I cheat myself out of hundreds of thousands of dollars? Will I completely sabotage my retirement later on in life?

As the number one person looking out for my family’s financial well-being, I believe these kinds of things are incredibly important when you’re picking the right retirement income strategies to go with. You owe it to yourself to do the best things for yourself that you can.

Let’s Begin – Defining Our Model’s Variables:

So similar to our example from before, you’ve got two choices:

- Invest $17,500 per year (before taxes) in a taxable account that we’ll use for retirement savings

- Invest $17,500 per year (before taxes) in a tax-sheltered retirement account (like a 401k)

To help re-build our model, we’ll need to make the following assumptions. Note that some of them have been revised from the first post we did:

- Assume we’re a married couple filing a joint return (tax status). You could also assume that $17,500 in savings is a combination of your savings (perhaps $8,750 from your account and $8,750 from your spouse’s).

- Unlike last time we will adjust for inflation using a 3% annualized rate. By doing this and putting the model into net-present dollars, we can make things easier by assuming the same retirement contribution each year, the same retirement withdrawal, etc.

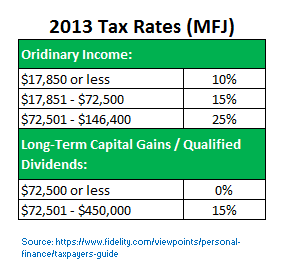

- Throughout the entire model we’ll be using the tax rates from 2013. Obviously there is always the possibility that the tax rates will change throughout the years. But since none of us can accurately predict what they will or won’t be 10, 20, 50 years from now, for now we’ll stick to what the current policies are.

- During your working years (pre-retirement), you’ll be in the 25% tax bracket with a modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) between $72K-$146K.

- Throughout the entire model using both methods we’ll assume all of our investments are the same and will make an average annualized 9% return (such as a low cost stock market index fund). After taking in the 3% inflation, this will reduce down to 6%.

- After 30 years of working and investing, we’ll declare retirement in year 31. Retirement contributions will cease.

- During retirement we’ll withdraw $48,000 per year ($4,000 per month) before taxes for living expenses. For the sake of illustration we’ll keep this withdrawal the same in both strategies; though we will also later in the post look at what they would be if you used the conventional 4-percent retirement withdraw rate.

- Also during retirement, assume the kids have moved out of the house by then and can no longer be claimed as dependents on your income tax return.

Pre-Retirement – The Taxable Model:

The first thing to consider is that when you say to yourself you have $17,500 to save in a tax-sheltered account, that would actually be only $13,125 in the taxable account. That’s because when you compare the two, you get to save it at your maximum marginal tax rate based on ordinary income. In this case, that’s at 25%.

$17,500 x (1 – $25%) = $13,125

(Or you could also say $4,375 lost to taxes)

Taxes on Dividends:

As suggested by Matt Becker, you’ll still owe taxes on your qualified dividend payments. On top of that you’ll probably also have a little bit of rebalancing going on. To quantify this, we’ll also take 3% of our total savings balance and pay the 15% capital gains tax rate on it.

Pre-Retirement – The Tax-Sheltered Model:

Things are simple on this side. Since you don’t have to pay any taxes on your contributions yet, the entire $17,500 just goes directly into the investment balance.

The Post-Retirement Years – The Taxable Model:

During retirement, going the Taxable route is actually the easier one to compute. In our model since we are taking out $48,000 per year to live on and all of this income is coming from long-term capital gains / dividends, we’ll owe 0% in taxes! This is because we have not yet exceeded the MAGI threshold of $72,500 where we then start paying 15%.

A minor point: The dividend income and capital gains from rebalancing would also not likely push us above the $72.5K MAGI threshold. So our tax rate will still remain at 0%.

The Post-Retirement Years – The Tax-Sheltered Model:

Now here’s where things get fun. Again thanks to reader Lucas for helping me to get this correct.

In our model we are withdrawing $48K from our savings for living expenses. Tax-sheltered income such as money you’d receive from a 401k plan is taxed as ordinary income.

The first thing we get to do is subtract a standard deduction and any personal exemptions. In 2013, these figures were a one-time number of $12,200 and $3,900 for each dependent ($7,800 for you and your spouse). Therefore our taxable income would be:

$48,000 – $12,200 – $7,800 = $28,000

Taking a look at the tax rates for ordinary income, we would calculate our taxes as:

$17,850 x 10% = $1,785

($28,000 – $17,850) x 15% = $1,523

$1,785 + $1,523 = $3,308

Notice how this figure is A LOT lower figure ($3,308 / $48,000 = 6.9%) than the 25% taxes we paid in the taxable model!

Another minor but subtle point: Because we are now no longer working and our savings is the only place that we can withdraw from to pay the taxes we owe, we’ll subtract the tax balance from our total savings balance each year.

The Results – The Difference Is Pretty Substantial!

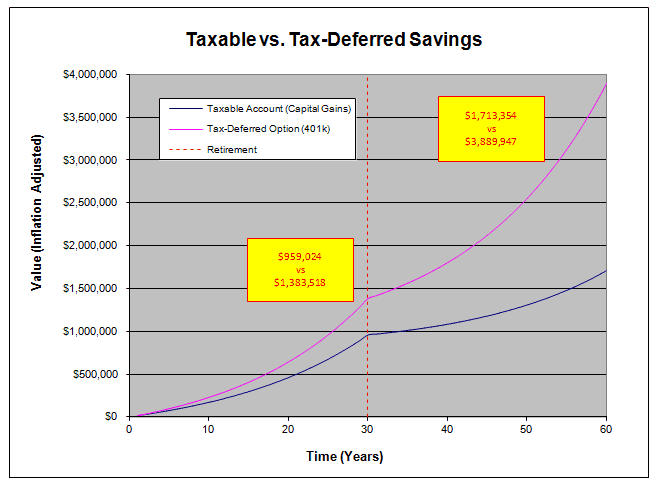

Taking in all these facts on how to calculate the taxes properly, inflation adjustment, and so on, does one investment strategy reveal itself as being more compelling than another? You bet!

Here are the results:

As you might guess, the tax-deferred strategy wins. And it wins by a long shot – both at the time of retirement and way out in the future (in our example 30 years after retirement).

What does this mean for you and me? Not only could we possibly live our entire lives with more wealth, but more importantly it means you’d be able to safely withdraw MORE money at the time of retirement and throughout your retired years.

To illustrate this point, let’s deviate from the $48,000 withdrawal figure we used in our example and instead use the conventional 4-percent withdrawal rule of thumb. How much money would we be able to take out from our savings each year?

- Taxable account: $38,361 per year or $3,197 per month after taxes

- Tax-deferred account:$58,648 per year or $4,887 per month after taxes

- That’s a difference of $1,691 per month! That’s no chump-change when you’re living on a fixed income.

Why Does the Tax-Deferred Strategy Win By Such a Long Shot?

Obviously the big advantage of a tax-deferred strategy is that you get to save more money during your working years (in our example at least $4,375 more each year). More capital right from the beginning will help to compound into larger returns later.

But a more subtle point is the tax treatment during retirement. Using the progressive tax system correctly, we can now see how we’re really only paying an average of about 7% taxes on our 401k plan during our retired years. This is a HUGE difference from the 25% taxes we paid out during our working years on the money we saved in the taxable account.

These two things combined are what drives such a large gap between the retirement income strategies.

What Does This Do for My Retirement Plan?

Clearly this changes a lot for me and makes things harder.

My original conclusion was that there would not be such a large difference between the two and that giving up some of that tax-sheltering would be a small price to pay for the prospect of early retirement.

NOW I can see that the price-tag on early retirement just got substantially larger! Say I was to go through with an early retirement by age 45 and used the taxable account strategy. By our example I could be cheating myself out of a potential extra income of $1,691 per month! That’s no small consideration.

If we look way out into the future I could potentially be costing myself almost $1.9 million dollars in accumulated wealth! That is crazy to think about!

So now that we have a more believable financial model, we return to our original question: Is it worth it? Can we in good conscious divert money from a tax-sheltered account to a taxable one for the sake of possibly taking an early retirement? What do you think?

Related Posts:

1) Could Early Retirement Planning Be Ruining Me?

2) Your Plan for How to Become Financially Independent

3) How Do You Compare to the Average Retirement Savings of Other Americans?

Images courtesy of FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Very interesting!

Now that I am self-employed, I have more incentive to save for retirement in my tax-deferred SEP IRA…so this is good to know. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with having different kinds of retirement savings and investments though. And who knows what kind of crazy tax rates we’ll have to pay when I retire in 25 years.

Hi Holly,

I actually think a lot of this would apply to someone who is self-employed. From what I’ve read, it seems like you have more lead-way to save more and choose what to do with it in a self-employed tax-deferred retirement account.

If the current trends continue, you should have nothing to worry about. Tax rates will be very, very lenient in the future. Check out what they used to be like just 10, 20, or 30 years ago: https://taxfoundation.org/article/us-federal-individual-income-tax-rates-history-1913-2013-nominal-and-inflation-adjusted-brackets

Of course I like your calculations 😉 I will point out one of your assumptions that isn’t quite accurate though, that may paint a very different picture for you.

There is a very easy way to get money out of a 401k/IRA before 59 1/2 without penalty. It is called a SEPP or 72T withdraw and it is much more substantial then most people realize.

What is SEPP? Basically the IRS allows you to setup a Substantially Equal Payment Plan for a minimum of 5 years or you hit 59 ½ (whichever is longer) to pull money out of an IRA without incurring the 10% penalty. The amount is still subject to taxes but those will almost be 6% or lower as in your example. The amount you can pull out is based on some IRS life expectancy tables and a reasonable interest rate (defined as up to 120% of the mid-term applicable federal rate (https://apps.irs.gov/app/picklist/list/federalRates.html) for either of the previous two months). If you want an idea of how much this would be for you, go to https://www.calcxml.com/calculators/72t and enter in your numbers and your age. For October 2013 the mid term rate is 1.93%, so 120% of that rate is 2.31%. So using the calculator for a 35 year old (with a 35 year old beneficiary) I get max of 3.4% withdraw rate via the amortization method with single life expectancy table (will go into details of the different choices in the next post). Waiting till 40 gives me a 3.6% withdraw rate. Both less then, but very close to the safe withdraw rate of 4%.

So basically you can get tax deferred savings and early retirement at a quicker point (due to tax savings) in one fell swoop 🙂

Hi Lucas,

Thanks again for all your help with putting this model together for the second time.

I have known about SEPP’s / 72T for a long time. Here’s a post I wrote about the topic almost 2 years. In the beginning of my My Money Design career I was certain that the 72T was going to be my magic bullet to an early retirement and my way out. But then I realized something very critical:

Say I pull out $100K from my 401k at age 45 using a 72T rate is 1.93%. According to the 72t calculator on Bankrate, I’d receive $3,685 per year (based on a 38.8 single life expectancy). The moment I do that, I’d be trading a potential future-value average annualized return rate of 8% and locking into that 1.93%. Is that a rate that I’d really like to lock into forever? Especially considering that rate is currently below the average rate of inflation at 3%?

Also, another thing that is not clear to me: Does your employer have any say whatsoever with the SEPP/72t process (since it is connected to a 401k)? I know my employer has made it virtually impossible to take out loans or make early withdrawals of any kind from our 401k.

So the AFR rate has NOTHING to do with your return on the money in your tax deferred account. It only has to do with how much you are “allowed” to pull out penalty free. So once you start a 72T withdraw based on the current AFR rate of 1.93%, ALL of your money in your 401k continues to earn whatever the market return is for your investments , 8% or more. The Feds just make you use a “projected” 1.93% return to calculate what you are allowed to pull out so that you “DONT RUN OUT OF MONEY”. Basically they just enforce a safe withdraw limit based on your age. Which is exactly what you would be trying to do anyway.

So your employer has nothing to do with SEPP/72T processes. However it isn’t really advisable to set one up on a 401k directly (there are a couple of extra restrictions). So what is better is to set it up on a IRA (which of course you can roll a 401k into). I am not sure why you would want to setup a SEPP while you were working though. You can do it, but all your money coming out would be taxed at your top tax rate though because you are not starting from $0

The additional kicker is that even once you setup a SEPP withdraw you are still allowed to contribute to a 401k or IRA (up to your “earned income”. So if you decide to do any part time work to decrease your income needs then you can just put a big chunk of the SEPP withdraw money back into a different IRA or 401k allowing your funds to grow even more.

Lucas, Thanks again for the clarification. In all the articles I had ever read I must have misinterpreted what the interest rate was to be used for. Your description makes a lot more sense to me. Out of curiosity why is it preferable to set this up on the IRA over the 401k?

I knew it was a bad idea, but had to double check to remember why. This is a little confusing, because it is allowed:

but it is not allowed if you are still an employee, and i think there is an additional age restriction (have to be 55 or older

https://www.401khelpcenter.com/401k_education/Early_Dist_Options.html#.UpUvgMRDt8E

Ah, life is not simple for the early retirement planners, is it? It’s really simple. You’ll just have to find a way to max out the tax deferred accounts then find the other ones. If only it were that easy…

Our strategy is still to use rental incomes to fund us until age 59.5 and beyond. Yes, you would have more money later on if you put everything in tax deferred accounts and didn’t touch it, but does that fit your plan and what will make you happy? If you can be happy with $1600 a month less but you get to retire years earlier, who’s to say that isn’t worth it?

Some days I might be willing to pay $1600/month to put it all behind me! 🙂

Great stuff MMD! I love how you really fleshed this all out (even without my input, haha. Sorry I still haven’t gotten back to you. Life, you know?) Anyways, another extension of this argument has to do with whether you should contribute to a Roth or a Traditional IRA (or 401k). The same concept of marginal vs. effective tax rate applies and it’s one that for some reason people continually overlook.

I agree with Matt. ROTHs are far to oversold. There are certainly cases where a ROTH would make sense, but in just a $ comparison, a Traditional IRA always wins because your average tax rates in retirement are going to be less then your Marginal rates now. The lower the tax bracket you are in now the more a ROTH makes sense, and there are some nice advantages of not having to deal with a SEPP to get money out of them, and not having to take minimum distributions. ROTHs are more of a after early retirement plan in my books though as your marginal rate would be lower, and you can store extra earned money into the ROTHs for easier access.

Wouldn’t you also need an SEPP to get your money out of a ROTH IRA? According to Fig 2-1 on the IRS Roth IRA guide, qualified distributions have to meet one of these 4 criteria to avoid the tax penalty.

You can always take out your contributions from a ROTH IRA (given you have had it open for 5 years or more) with no penalty and tax free.

For withdrawing earnings take a look at this link, it depends on the source of the funds. :

https://www.investopedia.com/university/retirementplans/rothira/rothira3.asp

I actually have not looked into SEPP on roth but i believe it applies as well.

this site references it as an option.

https://www.rothira.com/blog/what-is-rule-72t

Roth vs Traditional 401k? Were you somehow looking at my computer screen just now?? I actually just finished drafting that post and it will be scheduled in December …

Haha, I’m actually working on one of those too. May the best man win!

Interesting comparison! I am not in the States, but I do have similar options here in Canada, of course.

The way I would approach it (and have been told to from my father, who was FI in his early 40’s) is to max out all tax-deferred accounts and then move any overflow (if there is any overflow – but for FI/ER people there always is!) into a taxable account.

Your father was absolutely right, and this post basically backs that up. By using the power of tax-sheltering in the early savings stages, you end up with a principal balance that is way beyond anything you could have saved on your own in a taxable account.

Thanks for redoing this post! With complicated matters like these, taking an iterative approach with input from others makes a ton of sense. I’m glad you were humble enough to take the criticism of your commenters and I hope I exhibit the same when I need to!

Being humble is a big lesson that I’ve come to realize from blogging. Sometimes as webmasters when we stop pretending that everything we write is correct, we’ll actually learn something useful from our readers.

Just curious, did you account for the 10% penalty since your goal is retire before age 59 1/2? I’m not exactly sure how that 10% penalty is assessed but if it’s 10% off your pre-tax withdrawal from a tax-deferred strategy that would lop off $4,800 right there. I have a feeling it’s a bit closer than you’ve pointed out. Of course as Lucas mentioned, there’s also the SEPP/72(t) option for your IRAs to get around the penalty.

Hi JC,

Good point, but no the 10% penalty situation was not at all intended to be a part of this example. We just used 30 years as a nice round number and not to imply that the person in this example was younger than age 59-1/2. We could have done the same calculations with 35 or 40 years (to theoretically go past age 59-1/2) and had the same conclusions.

Nice job MMD!. I thought I’d done well find an extra $500k….looks like you found yourself a few million extra! 🙂