The following is a guest post from Matt Becker, founder of Mom and Dad Money. Matt is a proud father and husband, and his site is dedicated to helping new parents build financial security for their family.

Although Matt and I have somewhat different personal opinions in regards to dividend strategies, I thought it might be fun to invite him to take the stage and share his perspective on why he thinks Total Return Investing would be better. I’ve always maintained the message on My Money Design that there is more than one way to reach financial freedom. If you can keep an open mind and not reject something just because it is different than what you use, then maybe you might just learn something.

Go ahead Matt ….

If you have paid any attention to the investment world since 2008, you have undoubtedly heard of dividend investing. A dividend investing strategy is simply one in which an investor chooses to put his or her money in stocks that have a strong history of paying consistent dividends.

An alternative to a dividend strategy is called total return investing. With a total return approach, an investor is looking for returns from any source, including but not limited to dividends. Specific to stocks, this essentially means that an investor will view capital gains as an equally appealing source of returns and will proceed with the sole goal of maximizing returns for a given level of risk, without preference as to where those returns are coming from.

It is my view that a total return strategy is superior to a dividend approach in several ways.

Some Investing Terminology:

A dividend is a dollar amount paid to shareholders out of the company’s earnings. It is typically paid on a regular schedule.

Capital gains represent the difference between a stock’s purchase price and its sale price. So if you own one share of stock that you purchased for $1 and you sell it for $2, you would have a $1 capital gain. You can also have a capital loss if you sell for less than your purchase price.

When a dividend is paid, the value of the company drops by the amount of the dividend. So if a single share worth $10 pays out a dividend of $1, that share will then be worth $9. So while you receive immediate income in the form of a dividend, your potential for future capital gains is decreased.

A Case for Total Return Investing:

Where Have Stock Market Returns Historically Come From?

According to John Bogle in The Little Book of Common Sense Investing (Exhibit 7.1), over the past 100 years capital gains (represented in his numbers by earnings growth) have accounted for:

- 53% of stock market returns while

- dividends have accounted for 47%.

But over the past 25 years:

- 65% of returns have come from capital gains

- while only 35% have come from dividends.

Not only that, but the actual return from dividends has fallen, from 4.5% per year over the past 100 years to 3.4% per year over the past 25. Today, the overall US stock market has a 2% dividend yield.

Looking at these numbers, it becomes pretty clear that capital gains account for at least half of the returns that the stock market produces, but the trend is such that it’s closer to 2/3 of the returns over more recent history. Given these facts, understand that if you choose to focus on dividends rather than a mix of dividends and capital gains, you’re doing something similar to choosing to invest in bonds over stocks. There’s nothing inherently wrong with the decision, but you are limiting your long-term growth by focusing on a market sector that has historically produced smaller returns.

With a total return approach, you expose yourself to both dividends and capital gains. The increased diversity in source of return, along with an increased exposure to the higher-returning source, both serve to increase your chances for long-term growth.

The Importance of Diversification:

Very simply, the premise of diversification stems from the fact that we do not know where future returns will come from. We don’t know whether dividend paying stocks will outperform their growth-oriented peers, whether large stocks will outperform small stocks, or whether the healthcare industry is truly the place to invest for the future. But when we are properly diversified, we don’t have to know. We are exposed to everything, so assuming that there is growth somewhere, we will be in on the action. It is the single investment tool in your arsenal that allows you to decrease risk without sacrificing expected return.

With a total return approach, you can go all-in on diversification. Because you don’t have a preference for your source of returns, you are free to invest in any type of company you want. But with a dividend approach, you are by definition limited in your choices. Sure you can choose companies across different industries and different regions of the world, but the reality is that companies with a strong history of paying dividends all share certain characteristics. And there are many types of companies that you will never have exposure to because of your self-imposed limitations.

Total return investing maximizes your opportunity to use the most powerful investment tool available to you.

A Risk Story:

Among the most widely held reasons for pursuing a dividend investing approach is the appeal of decreasing investment risk. Intuitively it makes sense that stable companies that pay out a high percentage of earnings as dividends will have less volatility than companies who are keeping their cash internal and providing less immediate income to their owners. And over the last few years at least, this has proven to be true.

However, this approach to mitigating risk ignores the fact that your investment portfolio does not have to consist only of stocks. A good total return approach will use stocks as the main driver of long-term returns, with portfolio risk managed by the inclusion of other types of investments. By including assets in your portfolio that should behave differently than stocks, such as US Treasury bonds, you can achieve your desired risk tolerance without sacrificing the benefits of diversification.

It is important to view your your investment portfolio as a sum of many parts. Looking at any individual piece in isolation skews the purpose of that piece as part of the larger whole. Maximizing the particular purpose of each asset type, and diversifying across asset types with a proper asset allocation, is a more efficient and holistic approach to investment risk management.

The Impact of Taxes:

If you are investing only within tax-advantaged retirement accounts, then the question of tax efficiency is moot. But many investors are putting money away with the goal of early financial freedom, and that will likely necessitate the use of taxable accounts for a portion of your investments. In that case, the tax characteristics of your returns matter a great deal.

In this area, capital gains are more appealing than dividends. Dividends are taxed year after year, slowly eating away at your returns. Capital gains will likely be taxed eventually, but you have the ability to defer those taxes and use that saved money to earn you more in the meantime.

All Hail the Dividend Aristocrats?

One of the biggest arguments that I’ve seen in favor of dividend investing over a total return approach is the recent performance of the so-called dividend aristocrats. A “dividend aristocrat” is simply a company that has raised its dividends for at least 25 consecutive years. Certainly an impressive feat.

Many of the articles touting these specific stocks cite statistics showing that they’ve outperformed the S&P 500 over some recent time period, anywhere from the last 1-15 years. And they’ve done so while experiencing lower volatility, the primary definition of investment risk. Higher return for less risk. Sounds pretty great right?

As soon as you hear an argument like that, you should immediately have serious doubts. Risk and return are inextricably linked, and you just cannot decrease risk without decreasing expected returns unless you’re talking about simple diversification. But beyond that, do you know what else has had similar returns to the S&P 500 over recent time periods, and at much lower volatility than even the dividend aristocrats? Bonds. Simple, boring bonds.

The above chart, taken from Morningstar, shows the growth of $10,000 in two different funds over the past 15 years (5/30/1998-6/3/2013). The blue line represents an investment in Vanguard’s S&P 500 index fund (VFINX). The yellow line represents an investment in Vanguard’s Total Bond index fund (VBFMX). Very clearly, the bond fund has outperformed with much lower volatility.

The point here is that while a particular strategy might have worked over some arbitrary time period, that doesn’t make it a better long-term approach. Bonds certainly have a place in your portfolio, but should they completely replace stocks? I think most people would say no. And by that same logic, a dividend strategy shouldn’t replace a total return approach simply because of strong recent performance.

One last point on these dividend aristocrats. These are not magical companies whose performance never falters. Just like other companies, their fortunes can change. As a case in point, in 2009 there were 52 stocks that met the group’s strict criteria. As of 2012, there were 51. But of those 51, 13 were different than the original set. So over the course of just 3 years, there was a 27% change in the group’s composition. As always in investing, past performance is no guarantee of future returns.

How To Implement a Total Return Approach:

The simplest, and in my opinion the best, way to implement a total return approach is to use total market index funds. Investing in a fund that represents the entire US stock market will expose you to the entire range of risk and return that the market has to offer. You can do the same with international stock markets and with the bond and real estate markets.

But you don’t have to use index funds. If you like picking stocks, a total return approach simply expands the universe of stocks from which you can make your selections. If you have genuine stock picking skill, then the increase in choices should give you greater opportunity to allow that skill to benefit you.

Conclusions:

Whether you’re investing for long-term growth or you’re relying on your investments to provide today’s income, your goal is simply to have the money available to meet your needs. No rational investor should have a preference for the source of this money. Whether it comes from interest, dividends or capital gains is immaterial. What matters is that you achieve the desired level of income and/or growth at a reasonable level of risk.

While there are many ways to achieve this, it’s my belief that total return investing is the most efficient approach. It has the advantages of diversification across companies, diversification across sources of return, and tax efficiency. It takes full advantage of all market forces in play, while still allowing you to control overall risk through proper asset allocation.

Photo credits: julesjulesjules m / Foter.com / CC BY-NC-SA / freedigitalphotos.net

As you say, I don’t care where my returns come from. I just care that they are there 🙂

Definitely a good outlook.

Very well put Matt. I tend to lean towards a total return philosophy personally, but ultimately will take it where I can get it. Great point on diversification, so few do it and many think that by investing in a couple of stocks that they’re well diversified.

“ultimately will take it where I can get it”. That’s the definition of a total return approach! The return is all that matters, not the source. There is no magic to one source over the other, though there might be tax benefits that matter. And yes, diversification is crucial, though it also negates much of the impact of picking individual stocks, which I view as a good thing but others do not.

Haha, I have never before seen an author have a strong opinion on a topic, then have the data refute their strong opinion, but they still maintain their original opinion.

Priceless…

So, you are saying that total return is better than dividend investing. Then the evidence shows you that dividend stocks have delivered very good total returns. You refute those facts however, and keep your original thesis.

It is amazing how much trouble people have in connecting the dots when it comes to investing matters. You can have both capital gains and dividend income from dividend stocks – hence you get total returns on those. The data showed you that, and you chose to ignore it, because you do not have an open mind.

Oh and by the way, dividend stocks have outperformed since 1972:

https://www.dividendgrowthinvestor.com/2010/05/why-dividend-growth-stocks-rock.html

Thanks for the feedback. A couple of responses.

First, I never wrote that dividend stocks won’t earn capital gains. I also never wrote that they won’t earn “very good” returns, however you would like to define that. I have argued that those returns will be less efficient than if you take a total return approach. You say that my data refutes that, but you do not specify how. Maybe you would like to clarify.

I clicked through to your article, and the data was certainly interesting. I find it especially useful for the author whose study you cite that he compared dividend-paying stocks to non-dividend-paying stocks, as opposed to comparing to the entire index, which of course is what a total return approach represents. If he had in fact run the numbers for the entire index, he would have found that $100 invested in the entire S&P 500 in January of 1972 would have grown to $3668 by December of 2009 (I used the tool here to run the numbers: . That significantly outpaces both his “all dividend” approach ($2266) and his “dividend growers and initiators” ($2945) approach. So dividend payers did not outperform the entire market, they simply outperformed stocks that didn’t pay dividends and they underperformed the entire market. A total return approach is one that looks at the entire market, so the time period used here would seem to prove my point.

So if you agree that dividend stocks deliver total returns, what is the purpose of your article? ( You are essentially comparing total returns vs to div stocks which are also equities and also deliver total returns).

Your take on taxes is pretty flawed as well. You are correctly saying that in a taxable account, dividend income is taxed. However, you are failing to mention that an index fund has constant buying and selling of securities as investors decide to sell their stakes. The turnover is also caused by index committee adding and deleting stocks. If you look at S&P 500, the annual turnover can vary from 5% – 10% EVERY YEAR. When an index fund sells stocks and generates a capital gain, who pays the taxes on it?

As for the study, the beauty is in the details – the study compared EQUAL WEIGHTED returns for different dividend buckets. You are comparing to cap-weighted ones. This is not apples to apples comparison

Overall, I think your article would have been more impactful, if you simply mentioned that dividend investors should focus on diversification, avoid looking only at the dividend yield. But the comparison you are making, creates unnecessary tension.

I will of course agree that dividend stocks will give you a total return, as will all stocks. But I do not think that a dividend-focused strategy is the best way to achieve total returns. That is the point of the article. It’s no different than admitting that you could of course drive from Maine to Florida by route through Nebraska, but arguing that there is a more efficient route to take.

On index funds, I will not argue that some index funds are better than others, and there are certainly some that are less tax-efficient. But as two examples, neither Vanguard’s Total Stock Market Index Fund (VTSMX) nor their S&P 500 index (VFINX) have distributed any capital gains since at least 2003 (I can’t find data from before then, so it may be longer). So your point about taxes, while certainly relevant for some funds, is not a blanket statement that can be applied to all. There are very efficient index funds that work very similarly to what is illustrated in my example.

As for the study, I think it’s important to evaluate these things as much for what they don’t include as what they do. I’m not sure why he chose equal-weighted portfolios, but the fact of the matter is that you always have the option of investing in the market and if you had done so over the period studied you would have come out ahead of his dividend strategy. That’s not an unfair comparison. It’s actually very relevant and very important for investors to understand. I believe it was a disservice to leave it out.

In the end, if you can be successful with a dividend-focused strategy, then by all means go ahead. But I do think there has been a recent trend towards viewing dividends as a superior source of return, and I just don’t believe that the facts bear that out. I think they are a very important source of return, but not worth prioritizing over other factors.

Great to see importance of diversification highlighted in importance–couldn’t agree more.

Thanks Mike. It’s one of your most powerful friends.

Dividends are the only part of total returns that are always positive. Once the dividend is paid to you it can’t be taken away. Not by managerial stupidity running the company into the ground and not by the market heading South. Because they cannot be taken away, dividends also act as powerful buffers in down markets limiting your losses.

Coupled the above with the fact that, by your own admission, dividends account for between 35 and 47% of returns. Dividend payouts should not be underestimated.

Risk and return are linked, but they’re not 1:1 as you imply in your article. You can, in fact, increase returns while decreasing risk by researching your investments and only moving on a stock when it’s under or fair valued.

Segueing from dividend investing to index funds doesn’t seem like a fair comparison to me. Index investing, by definition, is the act of spaying money across the entire market without giving any thought to whether any individual investment is good or bad. Dividend investing if done right is a subset of value investing, which means that investment decisions are made by analyzing the underlying fundamentals of a company. This takes more effort than index investing and is not for everyone, but it will give you a chance at beating the market. Index investing, by definition, can never beat the market.

You make a good point about the importance of diversification, but there is nothing about dividend investing that rules out diversification. It’s a common stereotype (I don’t know where it comes from) that dividend investors shove all of their money into AT&T (or some other high yield stock) and that’s it. As a dividend investor, my goal is to have my money eventually spread out over 40 or so high quality investments.

Furthermore being a dividend investor doesn’t prohibit you from investing in real estate, bonds, P2P lending, futures, options, baseball cards, or anything else – thus further diversifying your portfolio.

Tax efficiency is not as simple as you make it out to be. Dividends are taxed, unless they’re in a retirement account – then they have the same tax efficiency as capital gains since the money is only taxed when it is pulled out from the account.

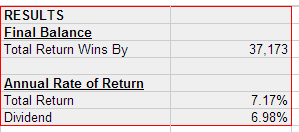

In a taxable account things aren’t as simple as your spreadsheet (which illustrates a 30 year bull market) makes it out to be. The 0.19% difference in the two strategies that you present will likely be eliminated (or more likely tilt in favor of dividend stocks) when down years are introduced. Remember – dividends are permanent, capital gains aren’t.

I’ll start by saying that if I were inclined to try my hand at stock-picking, I would certainly be in your camp on the value approach. It’s the most practical and consistently successful strategy out there and one I admire when done well.

With that said, the evidence is simply too strong that the vast majority of people are simply not good at doing what you say and “only moving on a stock when it’s under or fairly valued”. The number of people with the skill to do so over and over again over many years is very small. So I do not think that most people should try it, especially when there is such a good alternative.

As for index investing, I have a few thoughts. First, it is perfectly reasonable, and in fact appropriate, to compare any non-index approach to index investing. After all, when a low-cost index is easily available, then it wouldn’t make sense to do something different if you weren’t trying to beat it. Second, index investing, as the data shows over and over again, is far from average and far from not giving any thought to your investments. It’s a proven strategy that outperforms the majority of other strategies period after period. And by and large, a strategy that outperforms one period will underperform the next, which plays even more into an index strategy’s favor. Third, most people do not have a need to outperform the market. Most reasonable financial goals are perfectly attainable without above-market returns, at a much lower cost and time commitment and with much lower chance of underperformance.

But this is not about index investing, so let’s look at your other points. You say that dividends are the only part of returns that are always positive. I will say yes and no. Yes in that they are never negative, but no in that they can be taken away and a dividend stock can still have a negative return. They do not represent guarantees.

You also say that dividend payouts should not be underestimated. I could not agree more. They are an extremely important part of the stock market’s return and should be considered as such. I just do not think they should be the main focus.

You say dividends can act as powerful buffers in a down market. Sometimes true. But so can something like treasury bonds, with more consistency, and without sacrificing your ability to invest in the rest of the stock market.

You say that dividend investing is a subset of value investing. Why not use the whole set? Why limit yourself unnecessarily? If you have legitimate stock-picking skill, you are creating a self-imposed handicap as opposed to opening up the entire universe of stocks to your analyses.

On the point about tax efficiency, down markets give you the opportunity to tax-loss harvest, which lets you further defer gains or offset ordinary income. So I think the introduction of down years would actually again point in favor of capital gains.

In the end, I think that each individual needs to decide what their personal goals are and choose a strategy that most aligns with those goals. No single approach is right for everyone. But my opinion is that a total return approach has more positives on the whole than a dividend-focused approach. Thanks for the alternative opinion. It’s always helpful to get multiple points of view.

I kind of feel like dividends have been the hot topic over the past few years. I never paid heard much about them when I first started working and looking at stocks, but to be honest I really didn’t pay that much attention. I believe in a good mix of everything including non stock investments to keep things well rounded. I have notice that it’s easier to sell a group of people opposed to the stock market in general (charity board I serve on who have to manage investments for an endowment fund) are more open to dividend stocks. People who fear losing everything in the market like getting some sort of guaranteed return even if the overall trend is down. Not very scientific, but many investors go by gut feelings alone.

It’s important to remember that dividends are not guaranteed. They are certainly more reliable than capital gains, but they are far from guaranteed.

I certainly think that dividends are an important part of investing, but like you say a well rounded approach is best. I do not think that focusing on any one particular approach is the best way to do things.

No one can predict the future. I’ll say why not both, dividend investing and total return investing! 😉

A total return approach, by definition, looks to capture returns from any source. This includes dividends. I certainly hope this article didn’t come across as anti-dividend. Dividends are a very important source of returns and should be an important part of any stock-oriented strategy. I just don’t think they should be placed in a primary role ahead of other factors.

I think for the vast majority of people sticking with investing in index funds is the way to go. Even index investing still requires you to be proactive and monitor your accounts, albeit much less frequently than with picking individual stocks.

As far as the notion that most dividend investors aren’t concerned with total return, that’s another myth I’m not really sure where it started. Granted my main concern is a secure dividend that increases year in and year out, but in order to do that the company must also be growing year in and year out. With a company that is growing every year I’m also getting solid total returns.

Dividend growth investors are seeking to cover their expenses with income earned from dividends and therefore not have to touch the principle. What happens with a total return approach, especially one that is tilted more towards capital gains when you need to withdraw your expenses right after the stock market takes a 20%+ drop? Now you’re sacrificing your principle base for when the economy/stock market takes a turn back higher.

The reason a lot of people are gravitating towards dividend growth stocks is that they provide a return/income every quarter. This can provide a buffer for when the markets take a turn for the worse and keep you level headed. Is the company or dividend at risk? If not, the dividend can help you maintain your sanity in the darkest hour instead of succumbing to the typical panic mode that most investors do and cash out at exactly the wrong time. They’re then hit with the double edged sword of losing 20%+ of their capital and then not getting invested again until the markets are back at new highs. So they lost 20%, waited until the markets increased 50%, finally felt comfortable, made another 20%, then lost 35% in the next turn of the markets. That’s a losing prospect. Although dividend investors aren’t immune to this either and I can only hope that I’ll remain level-headed when the markets make their next big turn because I know that the company and the dividend are safe as far as I can tell.

Also using bonds even treasury bonds and extrapolating their performance from the past 30 years forward seems pretty outrageous. Interest rates have been on a general decline for the past 30 years leading to outsized gains. The yield on the 10 year treasury bond is currently 2.18%. Considering inflation has averaged around 3.5% you’re losing about 1.25% of your value every year that you hold that bond. As a double whammy interest rates have pretty much nowhere to go but up meaning declining values of your bond should you need/want to sell it. I would not be purchasing bonds in the current environment when the best case scenario is hoping that inflation isn’t higher than 2% per year over the next 10 years so you can eek out a small gain. Especially since the reported inflation number doesn’t include food or energy prices.

The assumption that you have to sell stocks and take a loss when the market is down is based on an assumption that you only have stocks in your portfolio. If you have a balanced portfolio, including an allocation to cash and/or bonds, then during a market downturn you can withdraw your funds from that portion of the portfolio and possibly even rebalance IN to stocks.

Your point about the psychological aspect of investing is an important one. One of the most important parts of success as an investor is understanding your risk tolerance and planning appropriately. The actions you describe would certainly be destructive to an individual’s investment, though it’s also completely hypothetical and not indicative of any general advantage dividend-focused investors have over others. But if that’s the approach that works for you, then good for you for figuring it out. I would again simply say that the same piece of mind could be created with other parts of your portfolio.

I will say that this notion that dividends are somehow this great protector against down markets is interesting to me. As one example, with a full awareness that a single example proves nothing, in 2008 Vanguard’s high dividend yield stock fund (VHDYX) dropped even more than the S&P 500. I understand the psychological aspect of dividends as safety, but it’s also important to understand that it doesn’t always play out that way.

I also think it’s interesting that people are so intent on not touching principle by taking dividends. Tell me this, what’s the difference between having stocks worth $100 that pay a $5 dividend, or me withdrawing $5 of “principle” from those same stocks? In both cases, the stocks will be worth $95 afterwards, so in reality they are the same. I’m certainly not anti-dividend, and in fact think that they are a very powerful pice of returns, but this concept that you’re leaving all of your principle intact with dividends ignores the very real fact that dividend payments lower the value of the stock.

As for bonds, since 1928 10-year treasury bonds have returned 5.41% (https://people.stern.nyu.edu/adamodar/New_Home_Page/datafile/histret.html). That’s a long period of time through many different market cycles. It’s true that yields are low right now, but neither you nor I are going to make our money off of short-term market predictions. My investment philosophy is based on long-term principles, not short term predictions that are impossible to get right again and again.

Some interesting points that you make. I’ve been investing in dividend stocks for a number of years.

Here are my thoughts vs S&P basket:

– There are a number of companies with poor business models who are unprofitable in the broader S&P. Dividend stocks typically are able to grow revenue and profit and cash flow, thats how they pay dividends

– Dividend stocks tend to be lower beta. When the market tanks, dividend stocks tend not to fall quite as hard, because they move less than the market. Stocks like MCD and others actually went up during 2008-2009. Thats important to make sure you don’t sell stocks at the worst times

– Dividend growth + initial yield ultimately fixes long term total return. What tends to happen is that stock prices of dividend growth stocks rise according to the amount of dividend growth, as cash return is priced based on risk. ie for a stock like McDonalds, if its dividend rises 10%, its stock price will also appreciate 10% as investors bid up the stock to get the same yield. You won’t get a situation where McDonalds yields 7% yield given its stability and business model. This leads to a situation where you can achieve total returns of close to 12-13% for high quality dividend payers with minimal volatility as they are low beta.

Index investing is certainly a sound way to invest, but ultimately, you are still taking a view on the largest positions in an index. You won’t lose your money investing in an index, but that no guarantee that you wont have periods of negative total returns either

Thanks for the comment. I have a few responses.

You conclude with: “You won’t lose your money investing in an index, but that no guarantee that you wont have periods of negative total returns either”. I 100% agree with this statement, but the implication seems to be that a dividend-focused approach will guarantee positive returns over all periods, which is not accurate. I responded to an earlier comment with the fact that in 2008 Vanguard’s high dividend yield stock fund (VHDYX) declined in value even more than the S&P 500. So it’s a fallacy to think that dividend stocks will inherently protect you in all market conditions.

You also pointed out MCD as an example of a stock that appreciated in 2008. Well I can point to an article written by one of the commenters above highlighting several dividend aristocrats with terrible performance in 2008: https://www.dividendgrowthinvestor.com/2008/11/worst-performing-dividend-stocks-so-far.html. I could also point out plenty of non-dividend payers who did well, as well as many that did not. But this gets into stock-picking which not only strays from the original point of the article, but is not something that typical investors (professionals included) have demonstrated that they can do well.

I do agree with your point about making sure you don’t sell stocks when the markets are tanking. Personally, I have other methods of achieving a balanced portfolio that are mentioned in the post, but the behavioral part of investing certainly has to be considered. If focusing on dividend payers is the best way for you personally to stay invested, then the cost of excluding the rest of the market may be worth it.

As for the comment about dividend stocks being low beta, I will simply point you to this article, which attempts to explain some of the misconceptions around what a low-beta strategy is actually achieving: https://www.gurufocus.com/news/153540/gmo–rethinking-risk-what-the-beta-puzzle-tells-us-about-investing

Finally, unless you’re Warren Buffet, you aren’t getting 12-13% returns anywhere at a lower risk than the overall market. While I will never argue that the market is totally efficient, it’s efficient enough to not let mispricings get anywhere near that level, especially when you’re talking about high-quality dividend payers, which are typically some of the most established and well-researched companies in the market. It is far more likely that you will get lower long-term returns with slightly lower volatility than you would with the overall market.